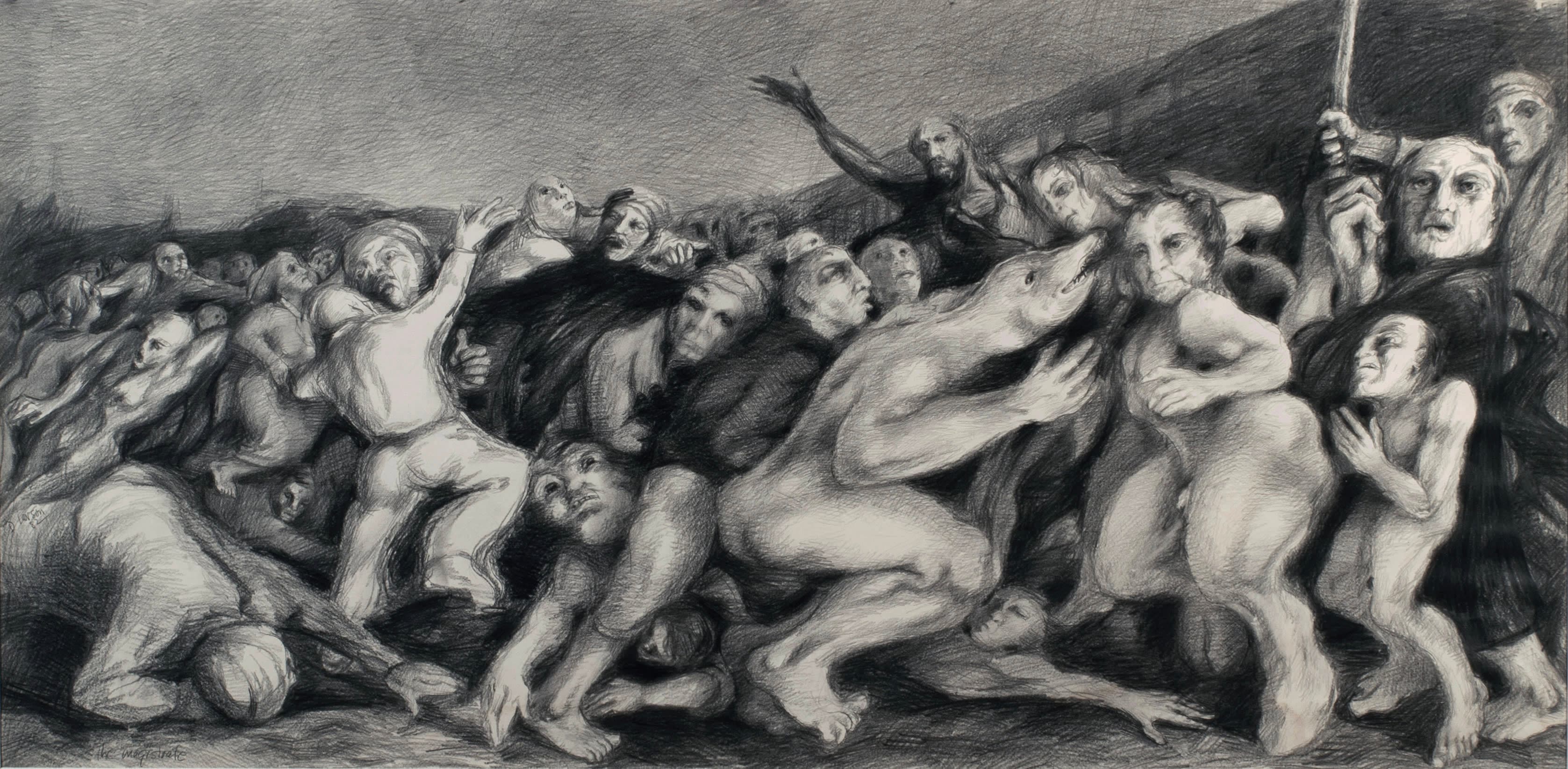

Drawings from the 1980s

The Magistrate

22"×48"pencil on paper

“The Magistrate” is loosely based on Francisco Goya’s monumental painting ‘The Second of May' in the Prado. You can read more about this work and other works by David that were inspired by Goya in this blog post - Soren Larson